St. Albertus Catholic School

As the fortunes of the city of Detroit have shifted, so have that of the east side neighborhood of Poletown. It was here that the city’s first Polish settlers put down roots in the 1850’s on what was then the outskirts of town, forming an ethnic neighborhood that grew and thrived with the city. Today though, the neighborhood is a shadow of its former self. Vacant lots of waist-high grass merge together into one big urban prairie, crisscrossed by crumbling streets and dotted occasionally with houses. With nothing to differentiate themselves by, the street corners all look the same with one exception: Canfield and St. Aubin streets. There stands a monument to Polish Detroit and the lasting impact the people of the neighborhood had on the city - St. Albertus Catholic Church.

Before the church, though, there was a school.

Father Simon Wieczorek, a Roman Catholic priest had traveled from his native Russo-Poland to America in 1868 to establish a church in the Polish settlement of Parisville, a town about 120 miles north of Detroit. One of the first things he did on arriving in Parisville was to establish a parish school to go with the church; Father Simon was a devoted teacher as well as minister, and believed that schools were essential to the health and growth of a church. In 1871 he traveled to Detroit to organize the first Polish Catholic church in the city, what would later become St. Albertus, the center of Detroit’s immigrant Polish population.

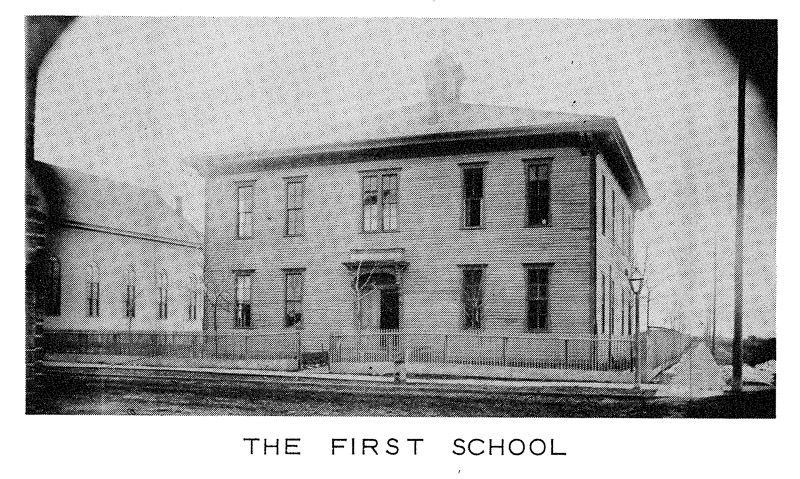

As plans were being drawn up for the church that year, Father Simon started a private school in a house on Willis and St. Aubin streets, teaching up to 40 children until the construction of the church in 1872 drew him away. After St. Albertus had been completed and dedicated, he immediately set about planning for a dedicated schoolhouse to meet the needs of the increasing number of pupils. Construction began in 1873 on a two-story wood frame building next to the new church. There was a difference in opinion, however, between the Father Simon and the leaders of the Detroit’s Catholic churches over the size and cost of the school – the parish was already deeply in debt, and it was worried that the school would push it into insolvency. Father Simon was eventually dismissed from his post over the way he handled the situation, and the school was paid for in large part by loans and donations from members of the church, at a total cost of $4978.37. In its first year, 1874, the school enrolled 97 students; the year after, enrollment more than doubled to 218 and continued to grow. Completion of the church and school was an important milestone for the early Polish community, as the quality of education attracted other families to the church.

Father John Wollowski, who had become pastor in 1879, also recognized the importance of St. Albertus’s school. He was convinced that the school needed a permanent, professional staff in order to thrive, so in 1879 he requested five Felician Sisters from Wisconsin, members of Catholic order deeply dedicated to the service of others and education. They arrived at St. Albertus School in December of 1879, where they found “118 boys and 100 girls curiously waiting for their services, with the parents either lukewarm or reserved in their attitude toward the new teachers,” according to Joseph Swastek’s centennial history of the church.

Whatever reservations the students and parents had about the new staff were eased quickly, as they warmed up to the new teachers.

“With the Sister's arrival, the enrollment increased annually during Fr. Wollowski's pastorate - 320 for 1880, 412 for 1881, and 474 for 1882. The Sisters brought with them not only proficiency, efficiency and stability but also their own textbooks and a bilingual (Polish and English) curriculum with a Catholic emphasis.”

“The curriculum of the elementary school embraced not only the fundamental three R's and religion but also ·such subjects as: natural history, general science, geography, History of Poland, History of the United States, general history, Polish language and literature, English language and literature, music (vocal), drawing, etiquette, gymnastics, knitting and fine needlework”

The growth of Poletown and other Polish neighborhoods soon filled the church and school of St. Albertus to overflowing, necessitating the construction of a new, grand cathedral in 1884 by Father Dominic Kolasinski’s. After construction of the new church, Kolasinski ran afoul of some parishioners and the local leaders by wanting to press ahead with construction of a new school, while the church was struggling financially. This precipitated his dismissal as leader of St. Albertus and the “Kolasinski affair,” a conflict between rival factions of parishioners supporting the priest and those backing his replacement, which resulted in small riots and the closing of church for 19 months.

From December 1885 to when the church reopened in June of 1887, schooling continued in the Felician Convent across the street, and the plans for new construction were shelved. After the quarrel was resolved, the school reopened and the number of students climbed to 650 in 1889, as well as 9 teachers. It wasn’t until 1892 that construction on a new school began, a $38,000 three-story brick building designed by John Schuman and Co and finished in November.

“Though it nearly doubled the parish debt, the new brick school built under Fr. Chodniewicz's supervision in 1892 was his most important contribution to St. Albertus Parish,” notes Swastek. “It had large classrooms on the first and second floors. The third floor consisted of a large assembly hall for meetings and programs, and for eventual division into classroom use if necessary. Steam heating equipment was installed in the basement.”

“The first principal of the new school was Sister M. Angela who remained in that post till 1895. Under her supervision, the classrooms were supplied with the latest teaching aids, and "dainty white curtains" decorated the windows to lend attraction to the teaching scene… The school followed a bilingual six-year program. In most subjects - religion, arithmetic, geography as well as Polish language and history – the instructional language was Polish. English reading, grammar and spelling were taught directly in that language.” Classroom size averaged 50 to 60 students, for which the sisters were paid $20 a month, and boarded out of the convent house across the street.

A few years later, in May of 1899, a school library was established, located in the fifth grade classroom. At first the books were kept locked in a cabinet, but as interest grew, they were moved onto shelves and soon numbered over 1,000 volumes of Polish and English books. Students and adults from around the community could check out a book for up to two weeks.

By 1904, over 1,500 students were enrolled at St. Albertus School. In the midst of the First World War, the third and final school was built, starting with the hiring of architect Henry J. Hill. The $250,000 school was completed in October of 1917 on the site of the original school, and was regarded as one of the finest and most modern schools in the city, with 24 classrooms, a library, and an auditorium that seated 1,000 students. There was one change in the curriculum though that signified the “Americanization” of Poletown: With the opening of the new school the primary language of instruction changed from Polish to English, though Polish was still used in some courses.

Peak enrollment reached 1,875 students in 1920-21. By 1932, enrollment had dropped in half to 899 students, and would never recover, despite the efforts of church leaders. Like the neighborhood around it, the school started to lose its Polish identity, as residents moved north to Hamtramck and the suburbs and were replaced by those of different ethnic backgrounds.

In 1945, the Archdiocese proposed setting up a high school at St. Albertus, but the pastor at the time, Father Ciesielski, talked them out of it, citing declining enrollment in the elementary school and the changing makeup of the neighborhood. He did not wish to saddle the shrinking congregation – only about 700 families by this time - with the expense of a large school he felt might never be fully used.

Enrollment was at only 383 in 1953, as Poles continued to leave the neighborhood, and just six of the 24 classrooms were in use. With just 90 students in 1965, keeping the school open was no longer an option. St. Albertus School closed permanently in June of 1966. Over 75,000 students had attended school there through three school buildings dating back to 1873.

After closure, part of the school building was leased to the City of Detroit until the late 1970’s for use as job training center for residents, helping the unemployed learn new skills. Poletown lost much of its Polish identity over the following years, with families leaving the area in droves through 1980. St. Albertus Church closed on June 3rd, 1990, 118 years after it’s founding, with just a small handful of members.

After closing, the church and school were purchased the Polish American Historical Site Association, a group made up of parishioners and volunteers who wanted to preserve the historic buildings. With donations and private funding, they reopened the church on an occasional basis, holding about a dozen masses a year. It’s extremely expensive to maintain such a large church, but despite some hardships they have kept the church going for over 10 years.

Today the school is vacant. Initially the new owners of the church had wanted to convert it into a senior citizen home, but there are no immediate plans to do so. Members keep a close eye on the school, securing it as best they can and cleaning the inside of debris regularly. The auditorium still retains much of its original beauty, though the paint has started to peel and some plaster has fallen. The hallways and classrooms are swept clean.

While it has been closed for nearly 50 years, the importance of St. Albertus School and the role it played in the development of the Poletown neighborhood is significant. It educated generations of immigrant and American-born Poles, maintaining a cultural heritage and language even as the world around it changed.