Fredrick Douglass Project Towers

There is a certain stigma that comes with living in a public housing project. The immediate impression is one of the poor, especially poor black Americans, crammed into looming tower blocks of brick and concrete. Cabrini-Green, the Robert Taylor Homes and other projects bring to mind drugs, broken windows, and gaping holes in the social fabric of a city. The term "projects" is a bad word. But it wasn't always that way.

The proposed construction of what would become the Brewster-Douglass housing projects drew national attention. The construction effort, which started in 1933, was the first federally-funded housing project for black Americans. At a time when segregation was the norm, the idea was met with skepticism, and in a few cases, violence from nearby white residents who feared their properties would lose value as blacks moved in.

Despite these obstacles, construction went forward, expanding in 1951 to include six 14-story towers.

Contrary to its current connotation, living in the projects was back then seen as a positive social status. "The people of the surrounding areas thought we were the elites," Barbara Battle Hunt, a 73-year-old former resident told the New York Times in 1991. Part of this was due to there being strict eligibility criteria requiring residents to maintain jobs, marital status, and a certain level of income.

The system started to break down in the late 60's and early 70's though, when residents with the wealth and means to move to the suburb did, causing the housing authority to become less selective in who they allowed to move in.

Despite renovations through the 90's, the population of the Brewster-Douglass projects continued to decline due to crime, drugs, and poor management. A 1991 HUD study found that the vacancy rate for Detroit's public housing was 42% - far above the national average of 3%. In an effort to consolidate resources, towers 3 and 4 were demolished in 2003

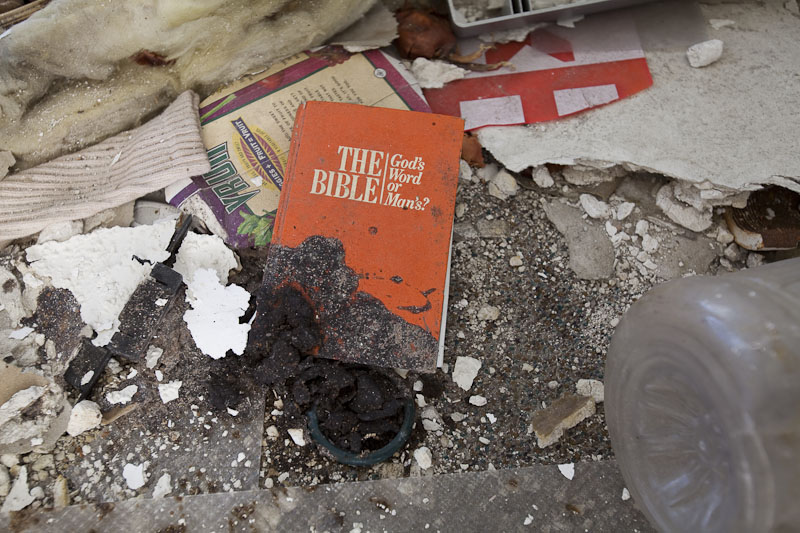

Articles from the early 2000's paint a pretty bleak picture of what life in the Brewster-Douglass projects must have been like: the majority of people living there at the time were senior citizens mixed in with welfare dependants, sharing space in poorly maintained buildings that stunk of urine and frequently had no running elevators. In 2008 the final residents were moved out, and the projects were boarded up.

In early 2012 the mayor of Detroit announced that the entire housing complex would be demolished to make way for a new development. Demolition began in the spring of 2014, and finished by fall.