Joe Louis Arena

Of Detroit’s many nicknames, few have endured for as long as “Hockeytown.” Detroit has a long history of hockey, dating back to the formation of the Detroit Cougars in 1926, which was renamed the Red Wings in 1930. For the past 50 years the Red Wings played at The Olympia, an arena located just outside of downtown along Grand River Boulevard. It was at the Olympia, also known was the Big Red Barn that the Red Wings grew into one of the dominant teams of the National Hockey League, winning the Stanley Cup four times in six seasons between 1949 and 1955 under the legendary Gordie Howe.

But by the 1970’s the Red Wings had fallen into a slump. During what became known as the “Dead Wings” era only 3,000 fans were turning out for games in an arena that could seat 14,000. The city was hemorrhaging jobs and residents to the suburbs. The Red Wings, like the city’s other professional sports teams started looking to the suburbs for a fresh start.

Mayor Coleman Young, the first black mayor of Detroit, was in his first term and desperate to keep Detroit’s sports teams downtown. Professional sports were one of the few things drawing people downtown, the reputation of which had yet to recover from the 1967 riots that had destroyed large parts of the city. The Detroit Lions football team had bolted first, moving to the Pontiac Silverdome in 1975. The Pistons basketball team was getting ready to leave, and the Tigers baseball organization was openly discussing relocating if they couldn’t get a new stadium.

Young believed that retaining the teams was the key to building momentum in revitalizing downtown, and to do that, a new stadium would need to be built. But the only developable land downtown was a five-acre plot wedged between the riverfront, the Cobo convention center, and a freeway. The Red Wings were not interested.

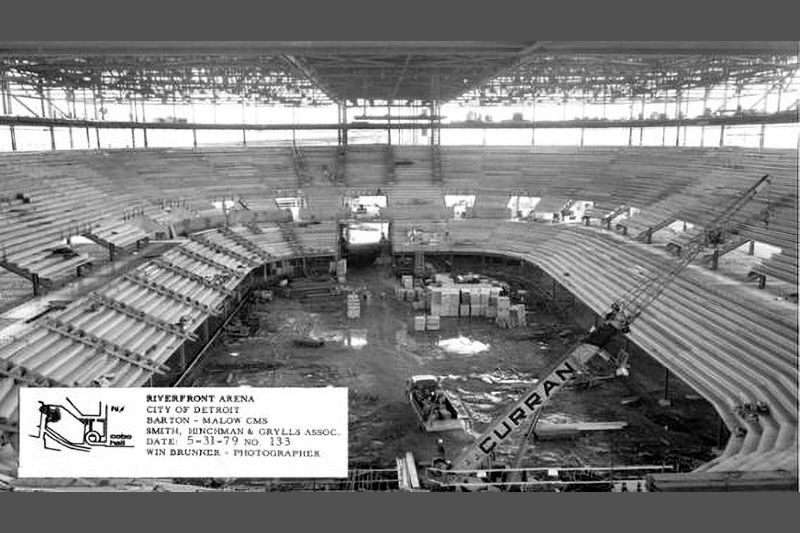

On April 1st of 1977, the Red Wings announced that they would be moving to Pontiac, a suburb of Detroit where a $15 million dollar arena would be built across from the Pontiac Silverdome. With few options and no firm commitment from either the Red Wings or the Pistons to stay even if the arena was built, Coleman Young pushed ahead anyways, starting excavation work on a 20,000-seat arena just a month later.

Critics howled about the high cost to the taxpayers, citing the lack of details and the estimated cost of $22 million dollars as signs that the project was doomed to be a white elephant. Adjacent to the site was Cobo arena, built in 1960 and already facing abandonment by the Detroit Pistons. Room for additional parking was practically non-existent. And due to the constraints of the site and the rushed development schedule, the design of the arena – described by the Detroit Free Press as “something akin to a fat, exotic submarine” would lead to complications that would plague the arena for the rest of its days.

In the end, however, Coleman Young’s bull-headed approach paid off. At a secret meeting in July of 1977, Young and the owner of the Detroit Red Wings met over coffee and in an hour worked out an agreement to keep the team downtown. The Red Wings signed a 30-year lease that gave them full control of the new arena and Cobo. The city would get $2 million dollars a year in rent and a cut of every ticket. It was a great deal for the Red Wings, and the city got to keep at least one team downtown.

Still, the new arena was not much of an upgrade from the Olympia. Originally designed for the Pistons, who did eventually leave for the Silverdome a year later, hasty modifications had to be made to accommodate a hockey team. The steps leading down to ringside were perilously steep. There weren’t many restrooms, and concessions appeared to be a distant afterthought. Red Wings players hated the arena. “It really wasn’t renovated and ready to go,” former Wing Paul Woods told the Detroit Free Press in 2017. “It didn’t make sense. You looked at the two buildings, and we were like, ‘Why are we doing this?’”

Over time, however, the arena grew on people. Named for Detroit boxer Joe Louis, the “Joe,” as it became known, had a quirky charm to it. It helped that after the team was sold to Mike Illitch in 1982, he began investing in improvements to the arena and the team, laying the groundwork for the Red Wing’s second act. Over the years the Joe would host political conventions, concerts, even a few Pistons games when their usual home at the Silverdome was unavailable due to tractor pulls or roof collapses.

But for most Detroiters what made the Joe memorable was the Red Wings of the 1990’s and early 2000’s. In 1997 the Red Wings won their first Stanley Cup in 42 years, winning again in 1998, 2002, and 2008. Maybe equally memorable was their bitter rivalry with the Colorado Avalanche, culminating in bench-clearing brawls dubbed “Fight Night at the Joe.”

As the Joe Louis Arena celebrated its 30th birthday in 2009, the building was showing its age. “I hope we don't celebrate a 40th anniversary there," Wings senior vice president Jimmy Devellano told Mlive.com. It was the fifth oldest arena in the NHL, and still suffered from the design shortcomings of its hasty construction. Chris Kuc of the Chicago Tribune described the arena and its “…lack of windows, deteriorating seats, an ever-present smell that has defied accurate description, wooden boards that send pucks careening as if bounced off rubber, spaghetti-like bundles of wires hanging from the ceiling, broken-down out-of-town scoreboards concealed by advertising banners, cramped dressing rooms, an antiquated press box and walls seemingly held together by duct tape and a prayer — these are just some of the charms of the venerable arena."

As downtown Detroit rebounded from decades of vacancy, the city’s sports teams came home too. The Detroit Tigers built a new stadium downtown in 2001. In 2002 the Detroit Lions returned from the suburbs, and even the Pistons were thinking about relocating. It was no secret that Olympia Entertainment, the owner of the Detroit Red Wings had been buying up land along Cass Avenue just outside of downtown. In 2012 the company unveiled plans for a new arena and entertainment district on Woodward Avenue called “The District Detroit.” Ground was broken on what would later be named Little Caesar’s Arena in September of 2014, with construction starting a short time later.

The last season of Red Wings Hockey at the Joe was in 2016-2017. Despite a lackluster showing by the team, missing the Stanley Cup playoffs for the first time in 25 years, most games had high attendance. Despite its shortcomings, people were sad to see the arena go. “It was the way the building was built, or something. I always felt in the Joe Louis Arena, and maybe it was because a lot of the old buildings used to have a promenade (in the seating areas) and it doesn’t, you always felt, well, sort of crammed in,” former coach Scotty Bowman told the Detroit News in October of 2016.

The contents of the arena were auctioned off in December of 2017. Seats were sold in October of 2018 for $50 apiece, with season ticket holders getting first crack at specific seats. Demolition of the arena began in the spring of 2019 and was largely completed by the summer. The land was given to an insurance company as part of a settlement from the city’s bankruptcy several years before.