Orchestra Hall

In the spring of 1913, a young American conductor by the name of Weston Gales was traveling by train to New York when a headline caught his eye. Gales had just returned from Europe, where he had been conducting orchestras across the continent. The Philadelphia Orchestra had played to large crowds in Detroit; a city that while cosmopolitan in many regards, lacked its on symphony. He immediately booked a ticket to Detroit, where he assembled a group of 40 musicians from theaters, cafes, and music schools. After several practice sessions, the ersatz symphony put on its first show at the Detroit Opera House in February of 1914, playing Beethoven’s Symphony No. 1 in C Major. The performance was well received, and members of the city’s high society established the Detroit Symphony Society. Within a short time, the Society raised $15,000 for Gales to assemble a small orchestra, which put on six concerts at the Detroit Opera House through 1914-1915.

In 1917 Gales left the Symphony, leaving it without a conductor and leader. After trying several visiting conductors, Russian Ossip Gabrilowitsch was chosen as conductor for the 1918-1919 season. The talented Gabrilowitsch came at tremendous cost and much fanfare, moving the symphony into the national eye. That year the symphony moved into the Arcadia Ballroom on Woodward Avenue. Gabrilowitsch found the Arcadia totally lacking in all regards, and demanded that a new purpose-built hall be constructed by next season or that he would leave.

A New Home on Woodward

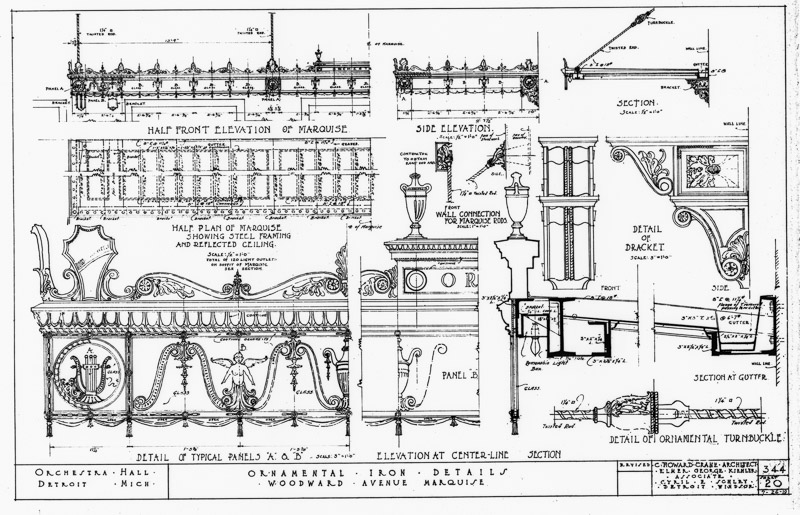

By April of 1919, planning was underway for the new Orchestra Hall. Unlike the theaters popping up all over downtown, the new venue would be located further up Woodward Avenue in midtown, on the site of the old Westminster Presbyterian Church. Noted theater architect C. Howard Crane was brought on as architect, with Walbridge & Aldinger as construction contractors. The timeline for construction left little room for error, with work expected to be wrapped up by October 1st.

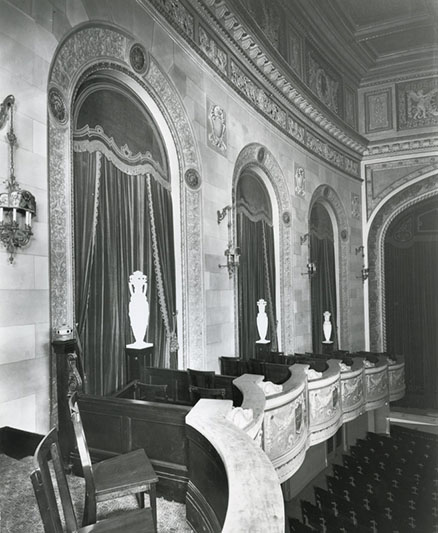

Construction on the $300,000 hall began before the architectural drawings had been completed. From the very beginning, the acoustics of the performance space were of particular attention. The footprint of the building conformed to the slant of Woodward Avenue resulting in a shape not a perfectly rectangular, with the north wall six feet longer than the south wall. Instead of correcting for this, Crane built the slant into the main hall, adding to the complexity of the acoustics. As the deadline for completing drew near, panic began to set in, and parts of the plan were redrawn or discarded. The ornate decorative elements were especially dense at the front of the hall, where work began, but began to thin out towards the back as workers raced to meet the deadline. Much of the exterior ornamentation was simply never built.

By August, construction was going night and day on the hall. Demand for tickets was so high that many of the 2,200 seats for performances were selling out months before the start of the season. Construction took exactly six months and three days, from the removal of the first brick from Westminster to the first concert. Even on opening night, October 23rd, 1919, the hall was not quite ready, and an extra $10,000 was spent removing the scaffolding for the first performance, and rebuilding it immediately afterward.

Opening night was a sold-out affair that made national news. "Thunderous applause, which lasted fully five minutes, greeted Ossip Gabrilowitsch when he appeared as director of the Detroit Symphony orchestra at its first concert of the season in the Orchestra hall Thursday evening," wrote the Detroit Free Press. The conductor had originally intended to use Beethoven’s "Dedication of the House" overture to open the hall, but the shipment of paper musical scores was late, and the national anthem was played instead. The 90-member orchestra performed works by Weber, Beethoven and Mozart, receiving multiple standing ovations from the audience.

By the early 1920’s, the DSO was one of the nation’s premiere orchestras, touring around the country. Despite offers from big cities out east, Gabrilowitsch elected to stay in Detroit, feeling it was one of the most promising music organizations in the country and he wanted to bring it to full success. Despite rising recognition, the Symphony lost money through the 1930’s, especially as the Great Depression took hold. Payment of taxes stopped in 1932, and after Gabrilowitsch died in 1936, support for the orchestra began to erode. By 1938, the Orchestra owed $30,000 in back property taxes.

Moving to the Masonic

In January of 1939, the Orchestra announced it would be moving into the Masonic Temple. Though only 20 years old, the hall was in need of expensive repairs, and it was cheaper to rent the much larger Masonic than continue paying for their own hall. The final concert was on March 16th, 1939. The audience finished by singing Auld Lang Syne, as the Detroit Free Press wondered "Those of the audience and orchestra who had permitted Orchestra Hall to become an indispensible part of their lives in the double-decade might have permitted themselves a passing shudder if they had given a thought to the ultimate fate of the stately building. Cinema? – parking lot? – bingo palace? –who knows? Sufficiently disturbing was the knowledge that after Saturday night Orchestra hall would no longer ring to the mighty measures of the masters."

After closing

After the orchestra left for the Masonic Temple, Orchestra hall was sold in June of 1940 to the City Temple, a "downtown spiritual and cultural center project." In November of 1940 Orchestra Hall reopened as the Town Theater under Jack Broder, a first-run movie and vaudeville venue. The hall was renovated, including new sound and lighting for motion pictures. The first showing was on November 8th of the film "Pastor Hall." In March of 1941, the Town switched to a revue-style policy due to problems getting first-run pictures, offering stage shows and B-movies.

Paradise

After the summer break, the Town Theater reopened in November of 1941 under the ownership of Ben and Lou Cohen with a new name - The Paradise Theater. The name reflected the changing racial composition of the city, as southern blacks moved north to find work in Detroit and other cities in the Midwest. Many settled in the neighborhoods of Black Bottom and Paradise Valley on the outskirts of downtown. With few venues featuring acts for black audiences, the Cohen Brothers began booking popular black musicians, including Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, Cab Calloway, and Jimmie Lunceford. The "colored" acts were successful, bringing in large crowds from the nearby black neighborhoods – and white ones as well.

The Paradise had a family atmosphere, with famous musicians and locals mingling freely backstage. Oftentimes patrons would stay the entire day, taking in the music and terrible B-movies. "The Paradise was open seven days a week, with a brand new show each Friday. It repeated three times a day, four times on the weekends… The week’s new star, be it Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Louis Armstrong, or any of dozens of great swing acts held rehearsals early Friday, working out their routines with other acts. It all had to be ready by 2 p.m." In later years, the Paradise Theater would be recognized as the center of Paradise Valley, where "Good jazz and a dance floor could be found there at any hour." A 1947 two-show appearance by Dizzy Gillespie caused a near-riot, when patrons of the first show refused to leave and ticketholders to the second show couldn’t get in.

In later years, the popularity of big bands began to fade, and competition with clubs and television ate away at profits. As the big acts moves elsewhere, the Paradise closed for periods of time. The Paradise announced in November that it was closing down for good on January 1st, 1952 and cancelling all upcoming acts. On January 29th, it was announced that the Paradise had been sold to the Church of Our Prayer for more than $250,000. Church of Our Prayer left in 1955, leaving the building vacant.

Ford Auditorium

The move to the Masonic in 1939 did little to stabilize the finances of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, which continued to struggle through into the 1940’s. The orchestra folded twice, in 1942 and again in 1949 due to lack of funds. In 1951, the orchestra re-formed under conductor Paul Paray, who would lead it for the next 20 years.

In 1956, the Detroit Symphony moved from the Masonic Temple into the Ford Auditorium, a modern 2,900-seat venue located downtown along the river. Though the orchestra was well received, the new venue garnered less flattering reviews. Originally designed for speaking events, the Ford Auditorium was poorly suited for orchestral music, and problems with the acoustics dogged the Orchestra for it’s entire run there. Where in the old Orchestra hall one could hear the turning of pages on stage from the furthest seats, the symphony struggled to fill the auditorium with sound, and as the years went on, struggled to fill the seats.

Vacancy

Though the symphony had departed Orchestra Hall, in some ways it never really left. Between 1952 and 1959, the Detroit Symphony returned to the closed Orchestra Hall 25 times to make recordings for Mercury Records, using its superior acoustics even as the hall slowly decayed. During one of these recording sessions in March of 1958, The Detroit Times described the state of the building: "Orchestra Hall, once the Grand Dame of Detroit Music, looked like a dirty, disheveled old hag in the faith half-light from the flies above the stage; walls scarred by peeling paint; carpets dirty and worn and in a number of seats once occupied by the cream of Detroit society, the springs had broken through the coverings… Part of the main floor seating had been roped off beneath the once-gleaming chandelier, now showing only a few dim bulbs alight and hanging from a loose cross beam… There was heat but no water. The cold spell had frozen some of the pipes and the cost of replacement was too heavy for a brief four-day occupancy of the once glamorous auditorium. Clean-up of the place for this visit had taken nine days."

When members went to check on the location before recording in January of 1959, they found that vandals had sacked the interior of the theater, smashing chairs and tearing curtains, leaving a foot of debris throughout the theater. The recording session was postponed, and eventually moved to the Ford Auditorium. In 1962, the hall was put up for sale at a cost of $120,000. It sold in March of 1963 to the Nederlander Theater Group, which owned several other Detroit-area venues and intended to renovate the hall for plays, ballet, and music to open in September. The project never got off the ground, and after sitting vacant for a number of years, the theater was sold to Gino’s, a chain of fast-foot restaurants in October of 1970.

Revival efforts

The first indication that Orchestra Hall was in danger came in a phone call to Paul Ganson, a 28-year old bassoonist with the DSO from a guard at a nearby bank, who called him in September to let him know that the water commission had sent men over to disconnect lines in preparation for demolition. Ganson, a native of Detroit, had been with the orchestra for just a year, but had heard other members describe the acoustics of Orchestra Hall in its glory days. He quickly began to organize preservationists and music enthusiasts in an effort to halt the demolition and save the building.

The task Ganson faced was monumental: By 1970 the hall was in terrible condition, with large parts of the decorative plaster hanging from the walls, soaked by water that came in through holes in the roof. Chair cushions had been burned by vagrants who crawled in through the sewers, looking for shelter and warmth in the winter months. But when musicians took to the stage and played, the acoustics came alive in a way that couldn’t be duplicated in the Ford Auditorium.

Recognizing the historic value of the building, Gino’s postponed demolition and offered to sell the hall back to the Symphony for $92,000, the price it had paid. By December, Ganson had organized the "Save Orchestra Hall Committee," and raised only $9,000. To raise awareness, the group made a short film titled "We Have Temporarily Lost Our Sound," which features a lone violin player in the wrecked auditorium. In September of 1971, the Dodge family donated $30,000 towards securing a $100,000 mortgage for the purchase of the hall. Repairing the roof alone was estimated to cost $22,000, with full renovation costing as much as $1.5 million.

By June of 1971, volunteers had begun cleanup work, removing debris in preparation for a concert to benefit the restoration. On first seeing the state of the hall, conductor Sixten Ehrling was taken aback, and when asked if the Detroit Symphony would play there sometime, he replied, "Even my grand children might not be around when that happens." Later that year, members of the symphony played for a group of potential investors as pigeons flew overhead and snow fell through holes in the ceiling.

By March of 1972 the full $100,000 had been raised after a sellout benefit dinner concert. The firm of Smith, Hinchman and Grylis were retained in 1973 to do a complete evaluation of the hall. Their report in June found that the hall was structurally sound, and could be fully restored in 10 to 12 months for $2.7 million. In fact, renovation would take 18 years, and eventually cost more than $10 million dollars.

The grass-roots campaign struggled through the 1970’s, with its funds dwindling down to just $105 at one point in 1973, but Ganson and his fellow volunteers continued their efforts. Restoration efforts began in 1974. The roof was repaired; electricity and heat were restored in 1976. A new stage floor was installed in 1977. The seats and ornamental plasterwork were restored over 1977-1981. The outer surface was repaired in 1982, a new fire system installed in 1983, and a new stage enclosure built in 1985. In 1988, the mahogany trim in the lobby and stairwells was replaced, and a new HVAC was installed.

Return

On October 23rd, 1979, the DSO returned to Orchestra Hall for its first concert since leaving 40 years before. Two years later, the DSO began to offer a concert series at Orchestra Hall, while still using the Ford Auditorium as it’s main venue. By 1987, restoration of Orchestra Hall had advanced to where the orchestra, dissatisfied with the Ford Auditorium, opened negotiations to move back into the hall permanently. The decision became official in February.

Initially there was some reluctance from members of the public to go to shows at the hall on Woodward Avenue, which at the time had a reputation for crime and seediness. Orchestra Hall sat next to several adult bookstores and liquor stores. Supporters of the project, however, believed that revival of Orchestra Hall could be the catalyst for growth along Woodward and throughout midtown. Over the summer of 1989, additional renovations were made to Orchestra Hall before the arrival of the DSO, including new carpeting, additional loge boxes, paint matching the original, and renovated restrooms. A performance of Mahler’s Third Symphony on September 21st, 1989 capped off a week of events celebrating the reopening of Orchestra hall.

Today, Orchestra Hall is at the center of a revitalized midtown, surrounded by new construction. In 2001, ground was broken on a major renovation of the hall and construction on a new addition, the Max M. Fisher Center for Performing Arts. The center opened on October 11th, 2003. Along with the nearby performing arts school, a total of $220 million dollars was invested in the community. A new commercial and residential complex was built across Woodward in 2005, and further development throughout midtown is currently underway.

Walk through Orchestra Hall today and you’d never guess just how close it came to being demolished to make way for a hamburger stand.